Lure of the mechanical watch

During each summer, I tend to find a new hobby or an interest. These hobbies are often things I've never done before. Around ten years ago, when Outi had just graduated and got a job as a doctor at a clinic near our summer cottage in Ilomantsi, I spent quite a few weeks learning the basics of jazz theory. I literally spent six hours a day, working through the basic modes, linking them to chords and coming up with exercises on guitar. A few summers later, I got my head around amateur astronomy and tried to learn all the constellations in the northern sky (I had much less success there; I still remember the scales and modes on guitar). Then marathons. A couple of summers later it was landscape photography, inspired by a trip to Scotland with my friend Mikko who happened to have an issue of Photography Monthly with him. The next summer I was learning about chess. Last summer it was soccer - small wonder since it was the world championship year.

During each summer, I tend to find a new hobby or an interest. These hobbies are often things I've never done before. Around ten years ago, when Outi had just graduated and got a job as a doctor at a clinic near our summer cottage in Ilomantsi, I spent quite a few weeks learning the basics of jazz theory. I literally spent six hours a day, working through the basic modes, linking them to chords and coming up with exercises on guitar. A few summers later, I got my head around amateur astronomy and tried to learn all the constellations in the northern sky (I had much less success there; I still remember the scales and modes on guitar). Then marathons. A couple of summers later it was landscape photography, inspired by a trip to Scotland with my friend Mikko who happened to have an issue of Photography Monthly with him. The next summer I was learning about chess. Last summer it was soccer - small wonder since it was the world championship year.

I realized such a pattern exists during summer holiday only recently. It appears that even if I often don't get very far with any particular topic, the whole process is extremely relaxing. It is as if building a completely new cognitive domain helps me to forget all the problems at work and "wipe the slate clean", so to speak.

The reason I realized this only now is that my interests have always made sense somehow before (well, excluding soccer of course). This summer, however, I have been fanatically finding my way around mechanical watches. The whole thing started as I had grown increasingly irritated about having to check the time on my cell phone, which has an irritating screen saver. Anyway, I started thinking that maybe it would be cool to have a cool watch and there I was. I've bought 4 books and a number of magazine issues (yes, indeed such magazines exist) thus far. I've ordered a mass of catalogues from a number of key brands.

It's not that surprising that I would find watches compelling, really. After all, watches represent pretty much what mankind has learned about mechanics to date. They are mechanical masterpieces and small works of art at the same time. What I find particularly compelling, however are the firms that make them.

Mechanical watch brands are precious things. The products cost a whole lot of money (there is no reasonable limit, really), and their consumers mostly do not understand the intricacies involved in their making. Yet the credibility of the brands is hard earned. We want to see in a quality watch brand a consummate passion for the practice of the art of watchmaking. To use MacIntyre's term, we want to see a brand watch as a product of internal practice (a practice practiced for its own sake) and not an external one (a practice practiced for accomplishing some other good extrinsic to the practice itself, money, for instance).

In the seventies, a plague, known as the "quartz revolution" rocked the fabled halls of mechanical watchmaking. Many quality brands got into financial troubles as quartz watches took their markets. Most of the companies changed owners. Some of them survived without major upheavals, some did less well.

Nowadays, the mechanical watch is yet again the pinnacle of creation. Companies seek to build their brands by trying to show an uninterrupted path of consummate practice lasting at least a hundred years. However, unlike the wine business, the families who founded the companies rarely own them any more. Some of the most respected companies had to rebuild their production after the seventies with the help of external investments.

The key to brand credibility here appears to be identity. Are the companies really the same as when they started out. Identity means sameness, and in the case of personal or organizational identity, this sameness means continuity over time. My identity involves a 10-year old me being the same person than me now, even if I am radically different person both physically and psychologically. The key question with watch companies is: are they the same, even if they had to rebuild their production, or if they had to change personnel altogether?

One interesting example is Breguet, a classical brand if any. The company invented the first wristwatch (yes, it appears that the watch in Pulp Fiction was indeed a Breguet). Its founder is regarded as maybe the greatest genius among watchmakers. Yet, in the seventies they were purchased by a non-interested investor and they fell into oblivion, until a heavy investment from the Swatch Group got them to their feet again. One arrogant jeweler noted that Breguet is "a brand in a ventilator".

This same jeweler also noted that a true aficionado could never buy a watch from a brand that did not manufacture its own movements. Actually, relatively few do nowadays - even Rolex only started doing this in the 2000's. This is another aspect of a precious brand: authenticity. It does not suffice to design great faces and cases, use reliable subcontractors and build a brand, as this would be external, not internal practice.

Another key aspect is exclusiveness. Among watchlovers and experts, Patek Philippe appears to be widely respected as the top brand in terms of technical finesse and style. However, as this reputation has spread outside the watchlover-discourse, for some this appears to take something away from the brand. Indeed, some people buy Pateks just because they are rich and want a good watch without really appreciating what they get (or so one might suspect). This has indeed happened with Rolex, which somebody said "is much better than its reputation".

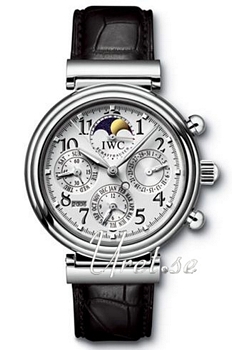

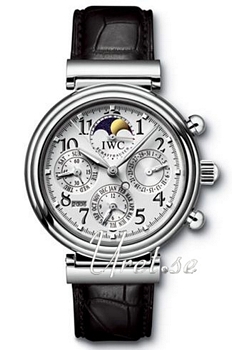

In any case, I have enjoyed this most recent excursion. Below are pictures of watches I find cool at this moment.

Jaeger-Lecoultre: Reverso Grande

IWC: Da Vinci

Audemars Piguet: Royal Oak

Breguet: Marine

During each summer, I tend to find a new hobby or an interest. These hobbies are often things I've never done before. Around ten years ago, when Outi had just graduated and got a job as a doctor at a clinic near our summer cottage in Ilomantsi, I spent quite a few weeks learning the basics of jazz theory. I literally spent six hours a day, working through the basic modes, linking them to chords and coming up with exercises on guitar. A few summers later, I got my head around amateur astronomy and tried to learn all the constellations in the northern sky (I had much less success there; I still remember the scales and modes on guitar). Then marathons. A couple of summers later it was landscape photography, inspired by a trip to Scotland with my friend Mikko who happened to have an issue of Photography Monthly with him. The next summer I was learning about chess. Last summer it was soccer - small wonder since it was the world championship year.

During each summer, I tend to find a new hobby or an interest. These hobbies are often things I've never done before. Around ten years ago, when Outi had just graduated and got a job as a doctor at a clinic near our summer cottage in Ilomantsi, I spent quite a few weeks learning the basics of jazz theory. I literally spent six hours a day, working through the basic modes, linking them to chords and coming up with exercises on guitar. A few summers later, I got my head around amateur astronomy and tried to learn all the constellations in the northern sky (I had much less success there; I still remember the scales and modes on guitar). Then marathons. A couple of summers later it was landscape photography, inspired by a trip to Scotland with my friend Mikko who happened to have an issue of Photography Monthly with him. The next summer I was learning about chess. Last summer it was soccer - small wonder since it was the world championship year.I realized such a pattern exists during summer holiday only recently. It appears that even if I often don't get very far with any particular topic, the whole process is extremely relaxing. It is as if building a completely new cognitive domain helps me to forget all the problems at work and "wipe the slate clean", so to speak.

The reason I realized this only now is that my interests have always made sense somehow before (well, excluding soccer of course). This summer, however, I have been fanatically finding my way around mechanical watches. The whole thing started as I had grown increasingly irritated about having to check the time on my cell phone, which has an irritating screen saver. Anyway, I started thinking that maybe it would be cool to have a cool watch and there I was. I've bought 4 books and a number of magazine issues (yes, indeed such magazines exist) thus far. I've ordered a mass of catalogues from a number of key brands.

It's not that surprising that I would find watches compelling, really. After all, watches represent pretty much what mankind has learned about mechanics to date. They are mechanical masterpieces and small works of art at the same time. What I find particularly compelling, however are the firms that make them.

Mechanical watch brands are precious things. The products cost a whole lot of money (there is no reasonable limit, really), and their consumers mostly do not understand the intricacies involved in their making. Yet the credibility of the brands is hard earned. We want to see in a quality watch brand a consummate passion for the practice of the art of watchmaking. To use MacIntyre's term, we want to see a brand watch as a product of internal practice (a practice practiced for its own sake) and not an external one (a practice practiced for accomplishing some other good extrinsic to the practice itself, money, for instance).

In the seventies, a plague, known as the "quartz revolution" rocked the fabled halls of mechanical watchmaking. Many quality brands got into financial troubles as quartz watches took their markets. Most of the companies changed owners. Some of them survived without major upheavals, some did less well.

Nowadays, the mechanical watch is yet again the pinnacle of creation. Companies seek to build their brands by trying to show an uninterrupted path of consummate practice lasting at least a hundred years. However, unlike the wine business, the families who founded the companies rarely own them any more. Some of the most respected companies had to rebuild their production after the seventies with the help of external investments.

The key to brand credibility here appears to be identity. Are the companies really the same as when they started out. Identity means sameness, and in the case of personal or organizational identity, this sameness means continuity over time. My identity involves a 10-year old me being the same person than me now, even if I am radically different person both physically and psychologically. The key question with watch companies is: are they the same, even if they had to rebuild their production, or if they had to change personnel altogether?

One interesting example is Breguet, a classical brand if any. The company invented the first wristwatch (yes, it appears that the watch in Pulp Fiction was indeed a Breguet). Its founder is regarded as maybe the greatest genius among watchmakers. Yet, in the seventies they were purchased by a non-interested investor and they fell into oblivion, until a heavy investment from the Swatch Group got them to their feet again. One arrogant jeweler noted that Breguet is "a brand in a ventilator".

This same jeweler also noted that a true aficionado could never buy a watch from a brand that did not manufacture its own movements. Actually, relatively few do nowadays - even Rolex only started doing this in the 2000's. This is another aspect of a precious brand: authenticity. It does not suffice to design great faces and cases, use reliable subcontractors and build a brand, as this would be external, not internal practice.

Another key aspect is exclusiveness. Among watchlovers and experts, Patek Philippe appears to be widely respected as the top brand in terms of technical finesse and style. However, as this reputation has spread outside the watchlover-discourse, for some this appears to take something away from the brand. Indeed, some people buy Pateks just because they are rich and want a good watch without really appreciating what they get (or so one might suspect). This has indeed happened with Rolex, which somebody said "is much better than its reputation".

In any case, I have enjoyed this most recent excursion. Below are pictures of watches I find cool at this moment.

Jaeger-Lecoultre: Reverso Grande

IWC: Da Vinci

Audemars Piguet: Royal Oak

Breguet: Marine

2 Comments:

Distractions are good.

I remember that some years back, I made a trip to London, we took the river cruise on the Thames. The end point is Greenwich, so we stopped by the observatory.

In the Greenwich observatory is a Time Gallery. Navigating ships involved a lot of time-keeping. Latitude wasn't a problem, but longitude was.

Thus, years of engineering research on clocks was launch. I supposed that this was a precursor to wristwatch technology, because both wrists and ships don't have stable physical locations upon which to rely.

The Time Gallery like a great place to visit. There is actually a small watch-museum in Espoo as well, which I visited with Iivari this autumn.

I've heard that navigation was the first context where time-measurement, more reliable than sunclocks. Thus speaks the Wikipedia:

In the 15th century, navigation and mapping increased the desire for portability in timekeeping. The latitude could be measured by looking at the stars, but the only way a ship could measure its longitude was by comparing the midday (high noon) time of the local longitude to that of a European meridian (usually Paris or Greenwich)—a time kept on a shipboard clock. However, the process was notoriously unreliable until the introduction of John Harrison's marine chronometer. For that reason, most maps from the 15th century through the 19th century have precise latitudes but distorted longitudes.

They key is to find a reliable oscillator. Galileo came up with the notion that weights of different masses oscillate with the same frequency as long as they are hung on strings of equal lengths (as long as you bracket out certain complicating variables - this practice in science is called idealization, which incidentally is key to Husserl's critique about western science being alien to the Lifeworld).

Hence was born the pendulum clock. In a wristwatch, the pendulum is replaced by a balance wheel, which rotates in two directions. The repelling force of gravity is replaced by a hairspring, which is plaved within the balance wheel.

Post a Comment

<< Home